For decades, technology has reshaped nearly every part of human life.

Problems that once took generations to solve were steadily chipped away by engineering, automation, and computation.

Yet money—arguably the most important coordination tool in society—remained stubbornly tied to old systems, even as the digital world advanced at full speed.

That tension set the stage for a monetary breakthrough that few initially understood.

Technology, Money, and the Shape of Power

Throughout history, advances in technology steadily reshaped what people used as money.

Each improvement solved problems that older systems could not.

As a result, entire societies rose or fell based on the monetary tools they adopted.

Metallurgy marked a turning point.

Metal forms of money proved more durable and reliable than beads, shells, or other primitive artifacts.

Later, standardized coinage improved trust and usability.

Gold and silver coins, unlike irregular metal lumps, were easier to verify, divide, and trade.

Over time, further innovations pushed gold to the top of the monetary hierarchy.

Gold-backed banking allowed gold to dominate global trade, while silver slowly lost its role as primary money.

If you’re ready to break free from banks, middlemen, and financial lies, read How to Buy Bitcoin: A Rebel’s Guide to Freedom and learn exactly how working people can start owning real money on their own terms.

Gold Didn’t Fail — Control Did

However, this system came at a cost.

Because gold had to be centralized for banking to function, governments stepped in.

Paper money backed by gold became more practical at scale, but control over the money supply followed soon after.

As governments expanded issuance and imposed coercive control, money gradually lost two critical traits: soundness and sovereignty.

Inflation became unavoidable. Trust eroded.

The monetary system shifted from serving individuals to serving institutions.

Key stages in this monetary progression include:

-

Primitive money such as shells, beads, and cattle

-

Metal money enabled by early metallurgy

-

Standardized gold and silver coinage

-

Gold-backed banking and global trade dominance

-

Government-issued money with centralized control

At every stage, technology determined what worked—and what failed.

The economic consequences were immense.

Societies that adopted sound monetary standards prospered, while those trapped in inferior systems paid dearly.

Strong Money Builds Empires — Weak Money Breaks Them

History offers clear examples.

The Romans under Julius Caesar, the Byzantines under Constantine the Great, and much of Europe under the classical gold standard all benefited from strong monetary foundations.

In contrast, others suffered severe losses.

Yap Islanders after the arrival of O’Keefe, West African societies relying on glass beads, and nineteenth-century China tied to silver all experienced economic decline once their money was exposed as weak or easily manipulated.

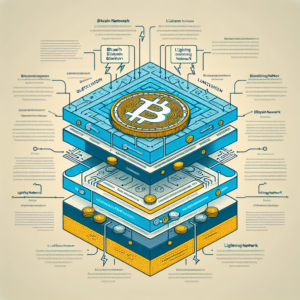

Bitcoin as a Monetary Breakthrough of the Digital Age

Bitcoin emerged as a new technological answer to an old problem.

It was born in the digital age and built on decades of earlier innovations.

Many attempts at digital money came before it, yet all of them failed to solve the core issues of trust, control, and scarcity.

Bitcoin succeeded where those efforts did not, delivering something that once seemed almost impossible.

This system did not appear overnight.

Instead, it combined multiple advances developed over several decades into a single working network.

Evaluating Bitcoin as Money

As a result, a form of money was created that could exist natively in the digital world without relying on banks or governments.

To understand why this matters, the focus must remain on Bitcoin’s monetary properties and its real-world economic performance since launch.

Just as a serious discussion of the gold standard does not require studying gold’s chemical structure, this analysis does not dwell on technical mechanics.

The emphasis stays on what makes the currency function as money.

Rather than examining code or network engineering, attention is placed on how Bitcoin behaves economically.

Its ability to store value, move across borders, and resist manipulation reveals far more than technical diagrams ever could.

For those serious about long-term Bitcoin accumulation, Swan Bitcoin offers automated buys, free withdrawals, assisted self-custody, and advanced services for families and businesses—start today and get $10 in free Bitcoin.

Payments Before Bitcoin: Cash or Control

Before Bitcoin existed, payment systems fell into two clear categories.

Each worked well in certain situations.

However, both carried limitations that technology could not overcome at the time.

Cash Payments: Final but Local

Cash payments took place directly between two people.

They were immediate, final, and required no trust in a third party.

Once cash changed hands, the transaction was complete.

No bank approval was needed.

No outside authority could reverse or block the payment.

However, this strength came with a major weakness.

Both parties had to be physically present at the same place and time.

As telecommunications expanded, this limitation became more severe.

People increasingly needed to transact with others far outside their immediate location.

Key traits of cash payments:

-

Immediate settlement

-

Final and irreversible

-

No third-party trust required

-

Limited to physical proximity

Intermediated Payments: Convenient but Fragile

Intermediated payments relied on trusted third parties.

These included checks, credit cards, debit cards, bank wires, money transfer services, and newer platforms such as Cash app.

In every case, a third party handled the transaction.

This model solved the distance problem.

Payments could be made remotely.

Funds did not need to be carried physically.

Yet these benefits came at a cost.

Trust became mandatory.

Transactions could be delayed, reversed, censored, or blocked.

Fees and settlement times added friction.

If you want a simple, beginner-friendly way to get your first Bitcoin, Cash App lets you buy instantly, start small, and move your BTC into self-custody when you’re ready.

Key traits of intermediated payments:

-

No physical presence required

-

Funds handled by a third party

-

Subject to delays, fees, and reversals

-

Vulnerable to censorship or failure

The Digital Dead End

Before Bitcoin, all digital payments required intermediaries.

This was not a design choice—it was a technical necessity.

Digital objects were not scarce.

They could be copied endlessly.

Because of this, true digital cash could not exist.

The problem was known as double-spending.

Without a trusted authority, there was no way to verify that the same digital funds were not being used more than once.

Only a centralized intermediary could track balances and enforce honesty.

As a result, cash remained trapped in the physical world.

Digital payments, by contrast, were permanently supervised.

Independence and finality could not exist online—until Bitcoin changed the rules.

The Breakthrough That Made Digital Cash Possible

After years of experimentation by programmers around the world, a solution finally emerged.

Many earlier attempts explored pieces of the puzzle.

Yet none could remove the need for a trusted intermediary.

Bitcoin changed that reality.

Solving Digital Cash Without Trust

By combining several existing technologies in a new way, Bitcoin became the first system to enable digital payments without third-party oversight.

For the first time, value could move across a network directly between individuals.

No bank approval was required.

No central authority was needed to verify honesty.

This achievement rested on one critical innovation: verifiable digital scarcity.

The First True Digital Cash

Unlike all earlier digital objects, bitcoin units could not be copied or duplicated.

Ownership could be proven. Spending could be verified.

Double-spending was prevented without relying on trust.

Because of this, Bitcoin became something entirely new.

It was not just digital payment infrastructure. It was the first true form of digital cash.

Dive into Bitcoin and the Future of Digital Cash Systems to understand how Bitcoin isn’t just digital money—but a revolution reshaping the way cash works for individuals, economies, and the global financial system.

What made this possible:

-

Elimination of trusted third-party intermediaries

-

Verifiable scarcity in a digital environment

-

Direct peer-to-peer settlement

-

Protection against double-spending without central control

For the first time, the properties of physical cash—finality, independence, and trust minimization—were replicated in the digital realm.

That shift marked a fundamental turning point in the history of money.

Why Digital Cash Matters in the Real World

Digital payments became the default for modern life.

However, that convenience came with hidden costs.

Because trusted intermediaries sat in the middle, sovereignty over money was steadily reduced.

The Weak Points of Trusted Third Parties

First, security risk was increased the moment an extra party was added.

A new failure point was introduced.

Theft, outages, and technical errors became more likely simply because more systems had to be trusted.

Second, surveillance and political control became easier.

Payments could be monitored, flagged, delayed, or blocked.

Justifications were often framed around security, terrorism, or money laundering, yet the outcome was the same: permission had to be granted by institutions.

Third, fraud risk increased and costs followed.

Disputes, chargebacks, compliance checks, and settlement delays were built into the system.

As a result, “digital payment” often meant “digital payment with strings attached.”

Quick summary of the drawbacks:

-

Added security exposure and technical failure risk

-

Exposure to surveillance, bans, and censorship

-

Higher fraud risk and higher transaction costs

-

Slower settlement and reduced finality

Money, Sovereignty, and the Need for Fungibility

A core feature of good money has always been the ability to be spent freely.

That freedom was historically expressed through two traits: fungibility and liquidity.

Fungibility meant any unit could be treated like any other unit.

Liquidity meant value could be exchanged quickly at market price.

When those traits were weakened, sovereignty was also weakened.

The Digital Shift Reduced Individual Control

Physical cash did not carry these digital weaknesses.

Intermediary problems were largely absent when cash was handed over in person.

Still, as trade and work stretched across distance, cash became impractical for everyday commerce.

As the world moved online, people were pushed toward systems that required permission.

Meanwhile, the shift from gold—money that cannot be printed—to fiat money—currency controlled by central banks—reduced sovereignty even further.

Inflation risk was increased, and long-term saving became harder.

The Goal: Cash-Like Payments, Online

Bitcoin was designed to fix this tradeoff.

A “purely peer-to-peer” form of electronic cash was aimed for—one that would not require trusted third parties.

In addition, a supply policy was embedded that could not be altered to create unexpected inflation for outsiders’ benefit.

To achieve this, several technologies were combined.

A distributed peer-to-peer network was used, single points of failure were removed, and transactions were secured through hashing and digital signatures.

Then, proof-of-work was used so that verification could be enforced without centralized trust.

Verification Replaced Trust

The system was built around verification.

A shared ledger was maintained across network participants.

Each transaction could be checked against balances, and consensus was required for updates.

New transaction blocks were added roughly every ten minutes.

To add a block, computational work had to be performed.

That work was costly to produce but easy for others to verify, which made fraud expensive and rejection cheap.

This mechanism was called mining.

Miners were rewarded with newly issued bitcoins and transaction fees.

In this way, the creation of new money was tied to the costly work of securing the ledger.

Fixed Supply and Difficulty Adjustment

A key design choice was made: the total supply schedule could not be changed by effort or demand.

Mining difficulty was automatically adjusted so blocks would remain near the ten-minute target even as more computing power joined the network.

That adjustment created a rare outcome.

The Inverted Incentive

As Bitcoin’s value rose, supply could not be expanded to match it.

Instead, more effort would only make the network harder to attack.

Bitcoin was made “harder” than previous moneys in this specific sense.

Rising demand did not create rising issuance.

Rising demand increased security instead.

Why Attacking the Ledger Is So Hard

A major asymmetry was created.

Recording transactions demanded increasing cost.

Yet verifying them was kept near-zero in cost.

Fraudulent blocks could be attempted, but they would be rejected cheaply by the network.

The attacker would be forced to burn real resources for nothing.

Over time, altering history became more expensive.

More energy would be required than the energy already spent, and that cumulative cost only grows.

As a result, the ledger was made highly resistant to dispute.

The Ledger Analogy and Ownership by Keys

Bitcoin’s ledger can be compared to the Rai stones of Yap in one important way.

Ownership changes were recorded socially, not physically moved.

Bitcoin, ownership changes were recorded digitally across all participants.

Control Through Keys, Not Custodians

Coins were represented as ledger entries.

Ownership was assigned to public addresses.

Control was secured by a private key, which functioned like a critical secret.

This design brought a major benefit: divisibility.

A fixed cap of 21 million coins was set, and each coin was divisible into 100,000,000 units called Satoshis

As a result, salability across scale was improved dramatically.

Incentives That Keep the System Honest

Honesty was made the profitable path.

Dishonest nodes would be detected and gain nothing.

Meanwhile, miners and users were financially rewarded for maintaining the system.

Even collective collusion was discouraged.

If the ledger’s integrity were destroyed, the value proposition would collapse.

Any “loot” from cheating would be made worthless by the loss of trust.

In this way, economic incentives were used as the enforcement layer.

Fraud was priced out.

Bitcoin as an Autonomous Network Firm

Bitcoin can also be viewed as an autonomous, rule-based system.

There were no management and no corporate structure.

Decisions were executed through software rules adopted by users.

Changes could be proposed, but adoption remained voluntary.

If major changes were forced, a split could occur and a knockoff network would be created.

Still, the unique incentive balance of the original network would be hard to replicate.

Absolute Scarcity and the Supply Schedule

Digital scarcity was achieved because ownership could not be duplicated.

A bitcoin could be transferred in a way that stopped it from being owned by the sender.

That had never been possible with ordinary digital files, which are copied rather than truly sent.

Beyond that, a stronger claim was introduced: absolute scarcity.

A cap was fixed, and it was designed to be practically impossible to raise.

The block reward began at 50 BTC, and it was programmed to halve roughly every 210,000 blocks (about four years).

Under that schedule, supply would approach 21 million by around the year 2140.

Even though blocks are not mined at exactly ten-minute intervals, the long-run schedule was designed to remain stable.

Variations were allowed in the short run, but the cap and declining growth rate were not.

Adoption, Price, and Early Milestones

Bitcoin began operating in January 2009.

A key milestone arrived when the tokens gained a market price in October 2009, which demonstrated that the network had passed an early market test.

In May 2010, the first widely cited real-world purchase occurred when 10,000 BTC were exchanged for two pizzas.

Over time, interest grew and monetization accelerated.

Early demand was driven by use in the network and a kind of collectible value among niche communities. Later, demand as a store of value increased.

This pattern echoed historical monetary evolution, where items often began as market goods before becoming money.

Transactions, Fees, and the Store-of-Value Pull

Network transactions grew rapidly over the years.

However, the number of transactions remained low compared to what might be expected from an asset with a large total market value.

That gap suggested heavy store-of-value demand, not just payments demand.

Limits on block size also placed a ceiling on daily transaction throughput.

Even so, rising adoption and rising value continued, implying that many holders valued the monetary policy and scarcity more than everyday spending utility.

Transaction fees rose as demand increased.

Early transactions could be processed with near-zero fees.

Later, fee markets emerged, and higher fees were used to prioritize faster inclusion.

Volatility and Why It Happens

Volatility remained high, and the reason was structural.

Supply was fixed and unresponsive to demand.

Without a central bank smoothing shock, price had to do all the adjusting.

In early adoption stages, demand swings are amplified.

Market infrastructure is also immature.

Over time, if liquidity deepens and long-term holders increase, volatility can decline.

However, as long as rapid growth continues, price may keep behaving like a high-growth asset.

Closing Thoughts: Digital Cash and Monetary Sovereignty

Money has always been shaped by technology.

When better tools appeared, older forms of money were left behind.

In the same way, digital life pushed payments toward intermediaries, and control was traded for convenience.

However, Bitcoin introduced a different path.

Digital cash was finally made possible through verifiable scarcity and a system built on validation rather than trust.

The Internet’s Native Money

As a result, cash-like finality was brought online, while third-party surveillance and censorship risks were reduced.

In addition, a fixed supply schedule was embedded into the system.

Inflation policy was removed from politicians, central bankers, and institutions.

Instead, issuance was made predictable, capped, and enforced by network consensus and economic incentives.

If this design continues to hold, a long-running shift in the history of money may be underway.

The same monetary pressures that once pushed societies from shells to metals, and from metal to gold-backed systems, may now be pushing the world toward a form of money native to the internet.