In the vast web of political scandal, corporate influence, and media manipulation, few stories remain as deliberately buried as those that challenge the power brokers behind the headlines.

While watergate is often framed as a triumph of investigative journalism, a closer look reveals unsettling contradictions—especially when the spotlight turns to those reporting the story.

One little-known book, censored into obscurity, dares to confront a towering figure of American media and raises troubling questions about who really controls the narrative.

The “Privished” Book That Exposed a Media Power Broker

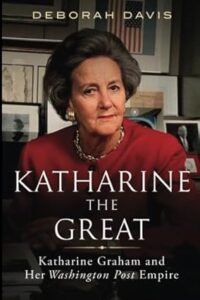

One especially intriguing book that touches on Watergate—but has been largely overlooked—is Katherine the Great by Deborah Davis. This critical biography of longtime Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham sheds light on a central media figure whose newspaper played a leading role in publicizing Watergate and taking down Richard Nixon.

First released in 1979 by Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, the book was swiftly withdrawn.

Only a handful of copies reached the public before it was pulped by the publisher.

This drastic move followed heavy pressure from Graham and her powerful allies, including figures tied to the CIA.

Michael Collins Piper found this episode especially revealing. The idea that a publisher would destroy its own book is shocking to many, yet it has occurred more than once.

In the publishing world, this act of deliberate suppression is known as “privishing.”

Katherine the Great is worth seeking out for those curious about what the mainstream media has tried to bury.

If a copy can be found, it may serve as a powerful addition to any collection on media influence and political intrigue.

The Power Behind The Washington Post

A quick look at Katharine Graham’s record is important here. The Washington Post Company has long been one of the most powerful media forces in America.

Not only did it publish the renowned newspaper, but it also owned Newsweek magazine for many years.

In addition, the company controlled numerous broadcasting ventures spread across the United States.

Although the Graham family held a major share of the company, they were not alone.

In fact, significant control was exercised by banks and financial institutions connected to the European-rooted Rothschild Dynasty.

Among these power players was Warren Buffett.

While famous as a wealthy investor, Buffett has often operated as a U.S. representative for the broader Rothschild financial network.

The Origins of a Media Dynasty

The roots of The Washington Post empire trace back to Katharine Graham’s father, Eugene Meyer.

He was a Jewish financier based on Wall Street and played a key role in shaping the paper’s future.

Meyer purchased The Washington Post in 1933.

This move came shortly after he stepped down as a governor of the Federal Reserve System—a position that placed him at the heart of U.S. financial power.

He was deeply connected to elite Jewish families.

His relations included the grand rabbi of France and the family behind Levi Strauss, the San Francisco-based clothing empire.

That company still ranks among the largest Jewish family fortunes in the world today.

Power Passed Through Marriage

In 1940, Eugene Meyer’s daughter, Katharine, married Philip Graham.

Though Graham came from modest beginnings, he had climbed the ranks to become a Harvard-educated lawyer.

Just six years later, Meyer took on the first presidency of the World Bank—an institution often seen as a tool of the Rothschild Dynasty’s global financial influence.

Around that time, Meyer handed control of The Washington Post to his son-in-law.

Graham was named publisher and editor-in-chief, a decision that would spark a dramatic shift in the paper’s legacy.

By 1948, Meyer formally transferred ownership of the Post stock to the young couple.

Yet, Katharine received only 30% of the shares. Her husband was given 70%, with his purchase financed entirely by Meyer.

Meyer reportedly believed no man should bear the burden of working under his own wife.

That belief would shape the power dynamics within the company for years to come.

The CIA Connection and Expansion of Influence

Under Philip Graham’s leadership, The Washington Post flourished.

Its media holdings grew, including the acquisition of the struggling Newsweek magazine and other properties.

After the CIA was formed in 1947, Graham developed a strong connection with the agency.

Journalist Deborah Davis described him as “one of the architects of what became a widespread practice: the use and manipulation of journalists by the CIA.” This covert program became known as Operation Mockingbird.

According to Davis, the relationship with the CIA was critical to the Post’s success. “Basically,” she wrote, “the Post grew up by trading information with the intelligence agencies.”

Through this relationship, the Post was transformed into an influential propaganda tool.

Its rise in national prominence was tightly linked to intelligence agency support.

This historical context is essential for understanding how deeply intelligence networks shaped American media. Davis’ book is available here if you want to explore it further.

Personal Strains and a Fractured Legacy

Despite the Post’s rising influence, tensions were growing behind the scenes.

By the time of Eugene Meyer’s death in 1959, a serious rift had developed between Philip Graham, his wife Katharine, and his father-in-law.

Meyer had begun to question the wisdom of handing over control of his media empire to Graham.

One major issue was Graham’s extramarital affair with Robin Webb, whom he supported with both a home in Washington and a farm outside the city.

Graham also battled personal demons. He was known for heavy drinking and displayed signs of manic-depressive behavior.

These issues were compounded by his frequent verbal abuse toward Katharine—conduct that occurred both in private and in public.

These challenges cast a dark shadow over the Post’s internal dynamics, raising doubts about the future leadership of the media giant.

Troubling Remarks and High-Level Tensions

Philip Graham’s emotional instability was later highlighted by Evan Thomas, a writer for Newsweek.

According to Thomas, Graham—who was not Jewish—often made anti-Semitic remarks.

These comments were reportedly directed at his in-laws, his wife, and even his own children.

This disturbing behavior came during a time when Graham maintained a close friendship with President John F. Kennedy.

That relationship took on added significance considering the president’s tense relations with American Jewish leaders.

Kennedy was viewed by some as insufficiently supportive of Israel’s interests.

In that context, Graham’s remarks and his ties to Kennedy likely raised eyebrows within powerful political and media circles.

Speaking Out and Losing Trust

According to Deborah Davis, Philip Graham had begun to raise concerns about the CIA’s role in manipulating journalists.

After his second mental breakdown, he reportedly expressed that this manipulation deeply disturbed him.

He even voiced these concerns directly to the CIA.

This shift in attitude marked a turning point. Graham began to break from the unspoken code of mutual trust and silence shared among elite newsmen and politicians.

Whispers soon spread that he could no longer be trusted.

Evidence suggests he was being watched.

Davis noted that one of Graham’s own assistants kept track of his erratic comments by jotting them down on scraps of paper.

Rumors of Mind Control and a High-Profile Breakdown

Some observers have questioned the true nature of Philip Graham’s famous mental collapse.

According to certain theories, the breakdown may have resulted more from the psychiatric treatments he received than from any actual illness.

At least one author has speculated that Graham might have been a subject in the CIA’s notorious mind-control experiments.

These programs involved the use of powerful, mind-altering drugs. If true, it would place his story within a much darker context.

What cannot be disputed is the profound effect the Graham family’s turmoil had on Washington.

The collapse of their marriage caused shockwaves across the political and media elite.

Given the Post’s influence and its deep relationship with the CIA, the fallout was immense.

Philip Graham’s Shocking Plans to Cut Out Katherine

In The Man to See (Simon & Schuster, 1991), Evan Thomas, a biographer of Washington Post attorney Edward Bennett Williams, revealed a startling confession from Philip Graham.

Graham shocked Williams by declaring his intention to divorce Katharine Graham.

More surprisingly, Graham planned to rewrite his 1957 will.

He wanted to leave everything that Katharine stood to inherit to his mistress instead.

This move would effectively deny Katharine the inheritance considered her birthright—an inheritance entrusted to Graham by her father.

The Battle Over Philip Graham’s Will and Control of The Washington Post

Despite Philip Graham’s repeated demands for divorce, his attorney Edward Bennett Williams delayed the process.

However, changing the will proved more complicated. According to Evan Thomas, Graham rewrote his 1957 will three times in the spring of 1963.

Each new version cut Katharine Graham’s share and increased the portion intended for his mistress.

Eventually, the final revision excluded Katharine entirely. A major conflict was on the horizon.

Katharine Graham was aware that something was wrong.

Deborah Davis reports that she told her attorney, Clark Clifford, the divorce settlement must grant her exclusive control of The Washington Post and all its associated companies.

The Breaking Point: Philip Graham’s Public Attack and Mental Breakdown

The situation reached a crisis when Philip Graham spoke at a newspaper publishers convention in Arizona.

There, he delivered a harsh speech criticizing the CIA.

He revealed insider secrets about Washington, even exposing his friend President John F. Kennedy’s affair with Mary Meyer, wife of top CIA official Cord Meyer (no relation to Katharine Graham).

Following this, Katharine Graham flew to Phoenix to retrieve her husband.

After a struggle, he was restrained in a straitjacket and sedated. Graham was then flown to an exclusive mental clinic in Rockville, Maryland, just outside Washington.

Tragic End and Legal Battle Over Philip Graham’s Estate

On the morning of August 3, 1963, Katharine Graham told friends that Philip was “better” and coming home.

She went to the clinic, picked him up, and drove him to their country home in Virginia.

Later that day, while Katharine was reportedly resting upstairs, Philip died from a shotgun blast in a bathtub downstairs.

Although the police report was never made public, his death was ruled a suicide.

Deborah Davis described the legal aftermath: During probate, Katharine’s lawyer challenged the validity of Philip’s last will. Edward Bennett Williams, hoping to keep the Post account, testified that Philip was not of sound mind when he made the final will.

Consequently, the judge ruled Philip had died intestate.

Williams then helped Katharine take control of The Washington Post without major legal obstacles, ensuring the will that left the newspaper to another woman remained out of the public record.

Speculation Surrounding Philip Graham’s Death

In her biography of Katharine Graham, Deborah Davis did not suggest that Philip Graham was murdered.

However, in interviews, she mentioned speculation that Katharine may have arranged his death or that someone reassured her, saying, “Don’t worry, we’ll take care of it.”

There is even speculation that Edward Bennett Williams might have been involved.

This shadowy story behind The Washington Post reveals deep, behind-the-scenes machinations.

It holds immense interest and remains highly relevant to understanding the corruption present in America’s mass media today.