Understanding Debts: Unveiling the Mathematical Realities

Debts, often perceived as legal or moral obligations to repay a specified amount, exist as mathematical concepts rather than tangible entities.

In the past, borrowing involved returning commodities like wheat, but in the modern capitalist world, debts are measured in dollars or cents.

Unlike physical wealth that can degrade over time, debts, governed by mathematical laws, exhibit a unique characteristic—they grow exponentially due to the inclusion of interest.

Interest, a payment for borrowing, expands the debt by adding to the principal amount, creating a continual rise in the owed sum.

Explore further as we dissect the complexities of debts, shedding light on the arithmetic driving our financial obligations.

Unveiling the Financial Realm: Understanding Mortgages, Bonds, and Debts

In the intricate landscape of finance, terms like mortgages, bonds, and debts often evoke varying images.

Are they forms of wealth or mere legal contracts?

Dive into ‘Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt‘ by Frederick Soddy for a groundbreaking exploration of economic paradoxes and the true nature of wealth in the modern world.

Let’s delve deeper into these financial instruments to demystify their nature and true essence.

1. Mortgages: The Legal Instrument

A mortgage might seem like a path to property ownership, but it’s essentially a legal instrument linked to loans.

Holders wield the right to acquire property titles if the specified loan terms aren’t met.

This underlines the contractual nature of mortgages, tightly woven within the financial tapestry.

2. Bonds: The Interest-Bearing Debt

In the realm of finance, bonds take center stage as interest-bearing debt certificates.

Their foundation lies in specifying a fixed dollar amount, forming a contractual obligation between the issuer and the holder.

Despite their financial significance, bonds do not represent wealth but rather are mechanisms of financial obligation.

3. Debunking Wealth Notion for Bonds and Mortgages

Are bonds and mortgages synonymous with wealth? Far from it.

Rather than embodying riches, these financial tools stand as legal claims, equipped to confiscate wealth when the loan terms are not met.

Their essence lies in contractual rights, not in tangible wealth itself.

4. Utility of Interest on Debts

What purpose does the interest on debts serve?

The interest, paid out in dollars, carries the power to procure tangible assets—essentials like food, clothing, and shelter.

This financial flowchart highlights the practicality of the interest accrued from financial instruments.

5. Authenticity of Bonds and Mortgages

Not all bonds and mortgages qualify as genuine loans.

In some instances, these financial instruments are procured through the creation of fictitious money.

This raises questions about their authenticity and the intricate nature of their creation.

Understanding the nuances behind mortgages, bonds, and debts unlocks a gateway to navigating the complex world of finance.

Beyond the surface, these financial instruments are more than legal contracts; they represent a convergence of financial obligations, interests, and contractual rights, shaping the tapestry of modern economics.

Unveiling the Ethics of Loans: A Closer Look at Genuine Loans and Interest Charges

The concept of loans and interest charges permeates the financial world, but their moral implications often spark debates.

Let’s delve into the heart of genuine loans, deciphering their moral standing, and understanding their role in fostering wealth creation.

1. The Essence of Genuine Loans

In the realm of genuine loans, the exchange involves real money—an embodiment of tangible purchasing power.

Consider this: If ‘A’ earns $1000 through productive endeavors, lending this sum involves a genuine loan where real wealth is transferred to another.

2. Moral Dimensions of Charging Interest

Is it ethically sound to impose interest on loans? For fictitious loans, the answer is a resounding “no.”

However, in the realm of genuine loans, ethical acceptance hinges on their purpose and reasonable interest rates.

3. Productive Loans: A Wealth Creation Narrative

A loan holds value when it fuels productive endeavors.

‘B’ borrowing ‘A’s’ $1000 for acquiring production instruments, such as machinery or tools, translates into a productive loan.

The interest paid on such loans represents a share in the wealth generated by these assets.

4. The Soundness of Genuine Loans

Genuine loans for productive purposes are financially viable as long as they adhere to reasonable interest rates and are repaid within the asset’s useful life.

This financial harmony ensures sustainability.

5. The Ethical Quandary of Non-Productive Loans

Christian teachings shun interest charges on non-productive ventures.

Loans used for purposes that don’t generate wealth stand in ethical dissonance, prompting a reevaluation of their moral standing.

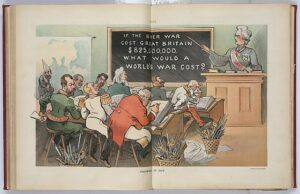

6. Deconstructing Loans for Destructive Ends

Loans directed toward destructive purposes, such as war funding, contradict ethical norms.

Charging interest on loans intended for destructive ends finds no moral ground in Christian principles.

7. Understanding the Dynamics of Purchasing Power

Genuine loans merely transfer purchasing power between individuals.

However, in contrast, fictitious loans orchestrated by banks create an artificial surge in purchasing power by generating money through lending, devoid of production or genuine wealth creation.

8. Justification for Interest on Productive Loans

The moral legitimacy of interest on genuine productive loans stems from the enhancement of wealth production.

The lender rightfully earns a reasonable share from the proceeds of newly generated wealth facilitated by the borrower’s productive use of the borrowed funds.

Understanding the moral fabric woven into genuine loans and interest charges sheds light on their intricate roles in financial ethics and wealth creation.

Exploring Equitable Investment: A Shift from Lending to Ownership

20. A Better Path for Savings: Direct Ownership of Industry

There exists a more equitable alternative for savings earmarked for the future beyond traditional lending methods. Instead, these funds can be invested to acquire direct ownership, wholly or partially, in an industry.

This direct ownership extends to owning crucial production instruments like buildings and machinery, transforming the saver into a direct stakeholder in the means of production.

21. Investment through Direct Ownership: A Common Practice

The act of investing in direct ownership is commonly known as acquiring a stake in a corporation’s capital stock, thereby obtaining a share in the ownership of its assets.

22. Understanding Capital Stock in a Corporation

Capital stock represents the actual investment, in dollars, made by the owners of a business, which the corporation utilizes to purchase essential assets like buildings and machinery.

23. Insight into Corporation Capitalization

Capitalization of a corporation encapsulates the initial owners’ invested dollars along with the earnings retained by the corporation.

These retained earnings constitute what is commonly referred to as the surplus.

24. The Form of Surplus in a Corporation

Surplus within a corporation generally doesn’t exist in the form of liquid cash.

Instead, these earnings are utilized to acquire additional assets like plants and machinery, expanding the company’s productive capacity.

25. Decoding Over-Capitalization

Over-capitalization or “watered stock” denotes the issuance of stock without a corresponding genuine investment of dollars into the company’s assets.

It represents an unethical practice of inflating the value of stock certificates without actual dollar investments.

26. Dividends: Returns to Capital Stock Owners

Dividends constitute cash payments made to the owners of capital stock.

They are rightfully earned as a share of the corporation’s profits and serve as returns on the owners’ investment in the business.

27. Ethical Necessity of Profits and Dividends on Honest Capitalization

Profits and dividends on honestly capitalized companies are essential.

Those who invest in ownership of production instruments deserve a rightful share in the new wealth generated by these instruments.

28. The Challenge of “Watered” Capital Stock

The devaluation of capital stock through over-capitalization or “watered” stock often arises due to actions by banks, particularly in major urban areas.

These institutions create money to lend to pool operators, artificially inflating stock prices beyond their true value based on the corporations’ assets and legitimate earnings.

By delving into direct ownership and its ethical implications, we unearth the importance of investing in a way that ethically rewards stakeholders in the creation of new wealth.

Rethinking Wealth: Impact of Bank-Created Money and Equitable Ownership

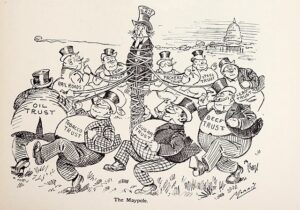

29. Bank-Created Money: A Catalyst for Dishonest Stock and Dividends

The arbitrary authority vested in banks to manufacture and annihilate money emerges as the primary force behind watered stock and deceitful dividends.

30. The 1929 Stock Market Boom and Bank-Led Price Manipulation

Between 1923 and 1929, banks lent between six and seven billion dollars to pool operators, inflating stock prices.

This vast sum, created through loans from various banks, aided those manipulating stock prices.

31. The 1929 Stock Market Crash: A Tale of Manipulation and Withdrawals

The crash in stock prices in 1929 stemmed from international financiers who flooded the market with vast volumes of stocks while orchestrating the withdrawal of colossal sums lent to pool operators and the unsuspecting public.

32. Equity in Direct Ownership vs. Lending

Investing directly in ownership ensures equity and societal benefit, unlike the practice of lending money and obtaining bonds or mortgages. Money invested in ownership shares both in earnings and risks.

33. The Ethical Aspect: Ownership, Consumption, and Fair Returns

Ownership investments entitle investors to a share of the new wealth produced annually, aligning with the instrument of production’s service to society.

However, they shouldn’t claim the original dollars along with their fair share of consumer wealth.

34. The Unsustainability of Bonds and Mortgages

Bonds and mortgages often entitle their owners to an unjust lion’s share of new wealth produced each year, along with a return of their original dollars.

Such loans extending beyond asset life are inherently unsound and unsustainable.

35. The Need for Widespread Ownership for Societal Growth

Widespread ownership of production instruments serves the best interests of all classes.

As producer goods wear out, new instruments must replace them.

Mass poverty results when incomes don’t facilitate savings for new investments in production instruments.

Understanding the dynamics of wealth creation through equitable ownership sheds light on the pitfalls of bank-manufactured money and the importance of fair and sustainable investment practices.

Understanding Wealth, Debts, and Labor: A Moral Perspective

36. Wealth and Consumption: A Single Use Scenario

Consumer wealth serves immediate human sustenance or transforms into production instruments.

Loans for fixed wealth can only be repaid from a share of newly produced consumer wealth.

37. Labor’s Role in Wealth Production

The direction of productive processes involves physical and mental labor.

Those contributing to production are rightfully entitled to a share of the created wealth.

38. Struggle for Fair Distribution: Bonds, Stocks, and Labor

When legal claims to consume wealth exceed a just proportion, meeting such claims hampers creating enough wealth to sustain laborers adequately.

39. America’s Labor Class and Suffering from Disproportionate Returns

In America, stockholders and bondholders often take precedence over laborers, receiving annual dividends while workers struggle with lower wages.

40. Moral Obligations of Corporations: Labor vs. Bondholders

Corporations’ moral responsibility entails just wages for labor as a primary obligation, followed by fulfilling obligations to bondholders and stockholders.

41. The Philosophy of Wages: A Departure from Equitable Returns

Wages are not viewed as mathematical debts akin to bonds, stocks, or mortgages in the context of modern capitalism.

42. An Argument for Annualized Wages: Biblical Principles and Labor

Christian philosophy advocates paying wages based on what labor produces annually, not merely for the hours worked, citing biblical parables to support this perspective.

43. The Prevalence of Fictitious Loans: U.S. Government Bonds and Banks

Most U.S. Government bonds are procured through fictitious loans from banks, granting holders titles to wealth consumption without contributing to its production.

44. The Phenomenon of Increasing Debts: Compound Interest Illustrated

Debts are mathematical entities that increase exponentially, exemplified by the saga of King Edward III’s loan, compounding over centuries into unimaginable sums.

Understanding these complexities sheds light on the dynamics of wealth, labor, and debt in societal systems, urging a reevaluation of ethical practices in financial transactions and labor remuneration.

National Debt Ownership and Taxation: Unveiling the Reality

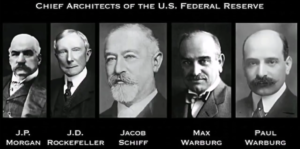

45. Federal Reserve Banks: The Principal Debt Holders

The Federal Reserve Banks and their members claim over $17 billion of the public debt, yielding approximately 4% in interest annually.

Taxpayers bear the annual burden of approximately $680 million in interest payments to these banks, who conjured money out of thin air to acquire these debts.

46. Tax Exemption and Debt Holders

These bonds remain free from any taxation, offering tax immunity to the bankers who own them.

47. Diverse Owners of National Debt

Apart from the Federal Reserve Banks, insurance companies, corporations, universities, and private individuals constitute the remaining creditors of our national debt.

48. The Question of Tax-Exempt Bonds: A Resounding No

Tax exemption for bondholders, irrespective of their status or claim to wealth, raises ethical concerns, calling for equitable taxation on all who claim ownership or wealth.

49. Anonymity of Bondholders: Shielded Identities

In general, the Government safeguards the identities of national debt holders, preventing public knowledge of these bondholders’ names.

50. Exacerbating Debt Burdens: A Multifaceted Approach

Debt merchants not only demand compound interest but also manipulate currency circulation.

Their astute manipulation ensures that debts paid during economic slumps command a higher value than those lent during periods of prosperity, intensifying the burden beyond mere compound interest.

51. War Bonds: A Legacy of Fictitious Loans and Persistent Debt

War Bonds symbolize loans based on fiction, spent on consumer goods destroyed decades ago. Yet, interest coupons from these bonds continue to perpetuate debt, illustrating the enduring repercussions of past fictitious loans.

52. Fictitious Loans: Mortgages and the Dilemma

Mortgages representing fictitious loans allow owners to claim a share of annually produced wealth, unjustly exploiting workers and gaining undeserved benefits.

53. Permissive Borrowing Practices: A Pervasive Issue

Unregulated borrowing, encompassing fictitious loans by nations, states, and cities for non-productive purposes, exacerbates economic and social woes.

54. The Toll of Unscientific and Unethical Practices

These practices, both unscientific and unchristian, heap unbearable burdens of interest payments on successive generations, perpetuating economic and social strife.

The complexities of national debt ownership, taxation, and borrowing practices underscore the need for transparency, equity, and ethical responsibility in financial policies for a sustainable economic future.

Unveiling the Nature of Modern Debts

- Abstract Obligations: In our contemporary world, debts no longer reflect tangible commodities but are numerical obligations, binding borrowers to repay both principal and interest in specific currency denominations.

- Legal Commitments: Bonds or mortgages serve as the legal vehicles binding borrowers to their financial commitments, establishing a formal obligation.

- Entitlement to Wealth: Holders of these financial instruments retain the legal right to claim a portion of the annually produced wealth, adding a financial dimension to ownership.

- Production Nexus: Consumer wealth, crucial for sustenance, relies inherently on the presence of production tools and machinery, underlining the necessity of instruments of production.

- Inherent Integrity: Genuine debts, grounded in legitimacy and aimed at productive purposes, stand as a hallmark of responsible financial undertakings.

- Moral Divide: While loans for productive pursuits maintain moral integrity, fictitious loans and those directed toward non-productive ends linger in the realm of illegitimacy.

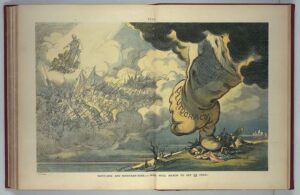

- Illustrative Non-Productivity: An example of non-productive debt emerges vividly in the form of war bonds, symbolizing loans aligned with destructive rather than productive purposes.

- Unattainable Reckoning: Accumulated interest on non-productive debts, notably war bonds, would inevitably surpass the tangible wealth of the world, representing an unachievable financial reckoning.

Deconstructing Debts: Navigating the Complexities of Financial Obligations

Navigating the intricate landscape of modern debts reveals a fundamental shift from tangible transactions to numerical obligations.

Bonds, mortgages, and their entwined complexities redefine financial commitments as mathematical quantities, blurring the line between tangible wealth and abstract obligations.

The distinction between genuine and fictitious loans, amplified by the moral and economic ramifications, becomes apparent.

As we unravel the intricate web of financial concepts, the journey doesn’t end here.

Join us in exploring the intricate tapestry of prices in our next blog post, delving deeper into the dynamic realm of economic values.

There’s always more to discover, more to learn, and more questions to answer in the world of finance and wealth management.