What if the very act of trying to save your wealth could destroy it?

Throughout history, civilizations have repeatedly fallen into the “easy money trap,” choosing abundant, consumable commodities as a store of value, only to watch their savings evaporate as producers flood the market.

The reason gold alone emerged victorious as the ultimate form of money isn’t a mystery of finance, but a lesson in brutal physical reality.

It possesses two unique properties that make it the only commodity capable of reliably preserving wealth across generations, silently defying the economic forces that crush all other contenders.

Why Gold Beats Other Commodities as Money

To understand why gold became the king of money, we have to look at the easy money trap.

This starts with a simple idea: every good has two kinds of demand.

-

Market demand – people want the good to use or consume it.

-

Monetary demand – people want the good as a store of value or medium of exchange.

When someone chooses a good as a store of value, they add monetary demand on top of market demand.

That extra demand pushes the price higher.

Take copper as an example. The world uses around 20 million tons of copper every year.

The price is about $5,000 per ton, so the total annual market is close to $100 billion.

If you want to understand the real risks behind gold investing, this article offers a clear breakdown of what every saver should know: Investing in Gold: Understanding Risks and Potential Losses

When Copper Wears a Monetary Mask

Now imagine a billionaire decides to park $10 billion of his wealth in copper.

His team runs around the world trying to buy 10% of the entire annual copper production.

Of course, the price rises as they buy. At first, this looks like a success.

The billionaire feels smart.

The asset he chose has already gone up in price before he even finishes buying.

Maybe others see this and start copying him. Copper looks like it is turning into money.

Why the Copper Billionaire Gets Wrecked

But the copper story does not end there.

The higher price sends a loud signal to miners, workers, and investors.

Copper suddenly looks like a great business.

The earth holds more copper than we can ever measure.

The only real limit on new supply is how much labor and capital people put into mining it.

The Producer’s Response: High Prices Cure High Prices

As the price goes up, more copper mining becomes profitable.

Production ramps up.

Let’s say annual output grows by 10 million extra tons and the price jumps to $10,000 per ton.

At some point, monetary demand slows.

The Great Unwinding: Speculators Become Sellers

People who bought copper to store value now want to sell some and buy other goods.

That was the whole point of saving.

Once that selling begins, the copper market drifts back toward its old balance: about 20 million tons a year at $5,000 per ton.

In fact, the price will likely drop below $5,000 as holders offload their stockpiles.

Our billionaire now holds copper worth less than he paid.

Most of his purchases were made at prices above $5,000 per ton.

Others who joined him later did even worse.

The Inevitable Outcome: Savers Lose, Producers Win

This is not unique to copper. The same pattern hits any consumable commodity:

-

Copper, zinc, nickel, brass, oil, and similar goods are mainly consumed, not stockpiled.

-

Global stockpiles are usually in the same ballpark as one year of production.

-

New supply is always coming onto the market to be used up.

When savers try to store large amounts of wealth in these goods, they run into a wall.

Their buying pushes prices up so fast that producers rush in, expand supply, and then crush the price again.

The end result is simple: Savers lose. Producers win.

The Inevitable Sequence: How All Commodity Bubbles Pop

This is the classic market bubble pattern:

-

Increased demand drives prices higher.

-

Rising prices attract more buyers, pushing prices up further.

-

High prices incentivize more production and new supply.

-

New supply crushes the price.

-

Everyone who bought at elevated prices gets punished.

Why Consumable Commodities Make Bad Money

For most consumable commodities, this story has repeated throughout history.

Anyone who chose them as money got burned.

Their savings were devalued.

Over time, the commodity slid back into its natural role as a market good, not a monetary asset.

Escaping the Producer Trap

For a good to be a real store of value, it must escape this trap. It must:

-

Go up in price when people demand it as a store of value, and

-

Prevent producers from increasing supply enough to crash that price.

Only then will savers who choose it be rewarded over time.

Their wealth will grow as others abandon weaker stores of value and copy their choice.

The runaway winner across history is gold.

If you’re just getting started with gold, this beginner-friendly guide walks you through a simple and reliable strategy for building long-term wealth: Gold Investing for Beginners: Reliable Investment Strategy

Gold’s Two Unique Physical Advantages

Gold dominates because it has two rare traits:

-

It is extremely chemically stable.

-

It does not rust or decay.

-

It is almost impossible to destroy.

-

-

It cannot be synthesized from other materials.

-

Alchemists tried for centuries.

-

The only real way to get gold is to mine it from the ground.

-

Because gold does not corrode, almost all gold ever mined still exists today.

The Immortal Metal: A Permanent Stockpile

Humans have been storing it for thousands of years in:

-

Jewelry

-

Coins

-

Bars

None of this gold is “used up” the way copper or oil are. It just keeps piling up.

The Impossible Alchemy: Why New Gold is So Scarce

At the same time, new gold is very hard to create. Mining is expensive, dirty, and risky work.

Returns get worse over time. The easy deposits are gone.

That means the existing stockpile of gold is huge compared to annual production.

For the last 70 years, gold’s annual supply growth has hovered around 1.5%, and it has never exceeded 2%.

That growth rate is tiny compared to most commodities.

If you’re thinking about buying physical gold, this step-by-step guide shows you exactly how to do it safely and confidently: How to Buy Physical Gold: Step-by-Step Guide

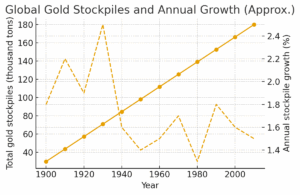

Figure 1: How Gold’s Supply Grows Slowly

Figure 1 tracks:

-

Total global gold stockpiles (in thousand tons)

-

Annual growth rate of those stockpiles (percentage)

Over the last century, total gold stockpiles have risen steadily, but the annual growth rate has stayed low and stable, mostly between 1–2%.

Even when demand spikes, new mining barely nudges the total s

Why Gold Escapes the Easy Money Trap

Now imagine that demand for gold as a store of value spikes.

The price rises. Mining firms respond and increase production.

Suppose they double annual output.

For a normal consumable commodity, doubling output crushes the price because new production dwarfs existing stockpiles.

The Vanishing Impact of New Supply

For gold, it is different.

Doubling production might raise annual growth from about 1.5% to around 3%.

That is still tiny compared to the existing hoard.

Even if miners keep up this higher production, the growing base of stockpiles makes the extra supply less meaningful over time.

It is practically impossible for miners to pull enough new gold out of the ground to truly flood the market.

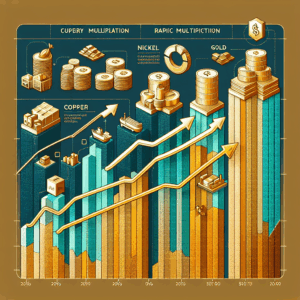

Silver: Strong, but Still Second Place

Silver is the closest rival to gold. Historically, it has had a 5–10% annual supply growth rate, rising to around 20% in modern times.

That is much higher than gold’s 1–2%.

There are two main reasons:

-

Silver can corrode and is used in industrial processes, so the existing stockpile is smaller relative to annual production.

-

It is more common in the earth’s crust and easier to refine than gold.

From Money to Metal: Silver’s Industrial Demotion

Because of this, silver held the second-highest stock-to-flow ratio for centuries.

It also had a lower value per unit of weight.

That made it perfect for smaller transactions, complementing gold’s role as “big money.”

Once the international gold standard arrived, people could use paper money backed by gold for any size transaction.

That killed the need for silver as day-to-day money.

Without its monetary role, silver drifted into being mainly an industrial metal and lost value against gold.

Silver may still carry the romantic image of “second place,” but in monetary competition, second place is the same as losing.

The Silver Bubble: The Hunt Brothers’ $1 Billion Lesson

Silver’s weakness shows up in one famous story.

In the late 1970s, the wealthy Hunt brothers tried to bring silver back as money.

They bought massive amounts of silver, driving the price up sharply.

Their theory was simple:

-

Rising prices would attract more buyers.

-

More buyers would push prices higher.

-

Eventually, people would demand to be paid in silver.

But they ignored the stock-to-flow problem.

The $1 Billion Lesson: When a Hoard Isn’t a Fortress

No matter how much silver they bought, miners and holders could keep selling more into the market.

Eventually, the price crashed. The Hunt brothers lost over $1 billion.

It might be the most expensive lesson ever in why stock-to-flow matters—and why not everything that glitters is gold.

If you want to explore the full story behind the silver bubble and the Hunt brothers’ downfall, classic reporting like Big Bill for a Bullion Binge.

This article offers a fascinating deep dive into how easy-money traps play out in real markets.

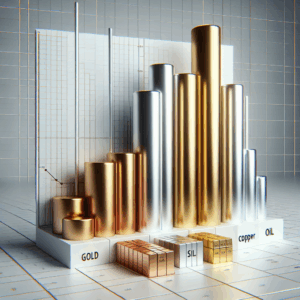

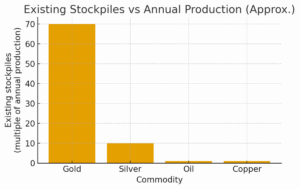

Figure 2: Why Gold’s Stock Is So Much Bigger Than Its Flow

Another way to see gold’s uniqueness is to compare existing stockpiles to annual production across several commodities.

Roughly:

-

Gold: ~70× annual production

-

Silver: ~10×

-

Oil: ~1×

-

Copper: ~1×

Why Gold Has the Lowest Price Elasticity of Supply

Because gold’s stockpile is so large and stable, it has very low price elasticity of supply.

That means: Even a large increase in price causes only a small increase in new quantity supplied.

Some examples:

-

In 2006, the spot price of gold rose by 36%.

-

For most commodities, that would trigger a big supply surge.

-

Gold mining output that year was 2,370 tons, about 100 tons less than in 2005.

-

It even dropped another 10 tons in 2007.

-

-

New supply was 1.67% of existing stockpiles in 2005,

1.58% in 2006, and 1.54% in 2007.

The Unshakeable Supply: Why Price Spikes Can’t Create More Gold

Even a huge rally in price does almost nothing to the flow.

The stockpile grows at nearly the same slow rate.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey:

-

The biggest annual jump in production was about 15% in 1923, which increased stockpiles by only around 1.5%.

-

Even if production doubled, stockpiles would rise only about 3–4%.

-

The fastest annual growth in stockpiles ever was about 2.6% in 1940.

-

Since 1942, stockpile growth has never exceeded 2% in a year.

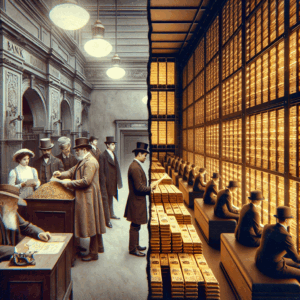

Gold’s Ongoing Role in Central Banks

Because of this slow, predictable supply, gold has kept its monetary role.

Central banks still hold about 33,000 tons of gold—roughly one-sixth of all above-ground gold.

Gold’s high stock-to-flow ratio is the core reason.

It protects savers from sudden supply shocks and inflation.

It cannot be printed, decreed, or faked at scale.

How Coinage and Banking Shaped Gold’s Power

As metal production grew, ancient civilizations in China, India, and Egypt began using copper and then silver as money.

These metals were hard to make at the time and worked well across time and space.

Gold was already treasured but too rare for everyday use.

It was in Greece, under King Croesus, that gold was first minted into regular trade coins.

That changed everything.

The Three Pillars of Monetary Dominance

Gold coins spread widely because:

-

They were durable.

-

They carried a lot of value in a small space.

-

They were easy to move and recognize.

Over time, human progress and sound money moved together.

Civilizations that adopted strong money tended to thrive.

Civilizations that embraced weak money often slid into decline.

If you want to compare the best online stores for purchasing gold, this guide highlights trusted retailers and helps you make smart buying decisions: Top Online Stores to Buy Gold: Ultimate Guide

The Great Uncoupling: Banking’s Double-Edged Sword

By the nineteenth century, improvements in banking and communication allowed people to transact with paper notes and checks backed by gold.

Now, payments could occur at any scale without moving the metal.

This made the gold standard possible and removed the need for silver as money.

The gold standard drove huge growth in global trade and capital accumulation.

But it also had a built-in flaw: it centralized gold in the vaults of banks and central banks.

Once that happened, governments could print more money than they had gold.

Whenever they did, they quietly stole value from savers.

Why This History Points Toward Hard Money Like Bitcoin

Gold shows us what a good monetary asset looks like:

-

It is hard to produce.

-

It has a huge, stable stockpile.

-

New supply grows slowly and predictably.

-

It resists the easy money trap.

Digital Gold: Bitcoin’s Programmable Scarcity

Bitcoin was designed to take these strengths even further.

Its supply schedule is fixed in code.

No miner, bank, or government can change it.

That is why many people see it as “digital gold.”

If you want to start moving a small slice of your savings into hard money, you can stack sats with $10 in free Bitcoin

This lets you begin with dollar-cost averaging into Bitcoin while also helping me keep fighting the fiat system through educational content.

Final Thoughts: Sound Money and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations

From copper to silver to gold to Bitcoin, the story is always the same.

When money is hard, people can save and plan.

Trade expands. Civilization flourishes.

When money becomes easy to create, bubbles form, savings are looted, and societies weaken.

Gold survived every competitor because it beat the easy money trap.

Bitcoin was built to carry that torch into the digital age.